Speech given at the Australian Ceramics Triennale in Sydney on 20th July 2009.

The title of this talk is taken from the chemical term for a molecule or atom in a highly reactive state.

Free radical reactions are apparently quite common, with combustion being an example that is particularly useful to potters, but the mental picture one is likely to form on hearing the term probably has more to do with alternative health supplements. If you take this particular extract or infusion, we are told, your body will expel the free radicals and you will become the picture of health.

In discussing contemporary ceramics, I think there are certain terms which count as free radicals and that our collective health would be better if they could be purged from the system. The one I’d like to talk about today is ‘innovation’.

At the moment innovation is simply everywhere.

The last time I looked, Arts Queensland was dedicated to ‘supporting and growing Queensland’s vibrant and innovative arts’ while Arts SA saw their support as aiding ‘ the artist to contribute to the development of their art form by embracing innovation and originality’.

Arts New South Wales ‘aims to support artists creat[ing] exciting and innovative work’ while the ‘Direction Statement’ issued by the West Australian government’s Department of Culture and the Arts, in the subsection headed ‘Creativity and Innovation’, states that they ‘ value imagination, freedom of expression and exposure to innovative ideas, events and debates’.

The Australia Council even has its own ‘Creative Innovation Strategy’,which recognises that ‘creativity is of increasingly strategic value to nations such as Australia in making the transition to innovation and knowledge-based economies’, a sentence which I’m pretty sure was written by one of the hollow-men.

Given all this emphasis on innovation, one would be forgiven for thinking that it is all around us. Yet, I would argue that truly innovative work is rare, and when it does appear it certainly isn’t at the whim of government policy. The reality is that innovation often occurs as a reaction against prevailing trends, something which tends to disqualify it from being a product of bureaucracy, formulated by a committee, celebrated in a mission statement and appearing as the result of a grant.

Normally, when one thinks about innovation it is something new, and not about something old, that springs to mind.

A friend of mine who worked at the National Gallery in Canberra used to say, ‘we’ve got lots of new crap, but not much old crap. The other galleries have got much better old crap.’

And, at least in terms of ceramics, he was right.

It’s very hard to compete with the benefaction of Herbert Wade Kent in his gift of ancient Chinese ceramics to the National Gallery of Victoria in 1931 — this Sung dynasty vase was Kent’s most prized possession, so much so that he requested he be buried with it. It was obviously not an entirely serious request, but it’s good to keep in mind that just because a pot goes into the ground it doesn’t mean it won’t pop back out again, a fact that Kent was well aware of, given the provenance of much of the ceramics he collected.

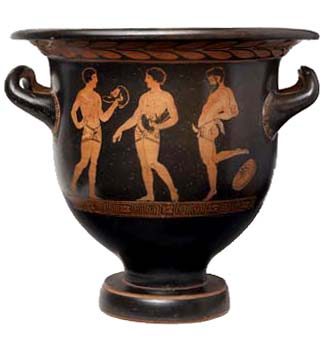

Another example of exemplary old ceramics is this fourth century BC krater, acquired by the Nicholson Museum at the University of Sydney in 1945. This pot was featured in the ‘Jewel in the Crown’ segment of Radio National’s Artworks programme earlier this year.

The senior curator at the Nicholson, Michael Turner, has pointed out that although it seems to depict three warriors in a state of sexual arousal, two of whom are holding the heads of vanquished foes, it actually shows three actors preparing for the performance of a play. The phalluses are part of the costumes worn in a performance dedicated to Dionysus, the God of exstasis, a term describing a state of heightened or altered experience and from which we derive the word ‘ecstasy’. The theatre, drinking wine, having sex were the sorts of activities that took one out of oneself. Since the pot was also a funerary urn, maybe the deceased just wanted to be reminded of the things they enjoyed when they were alive.

It is complex piece; amusing, sophisticated and beautifully crafted. It is also deeply traditional, in that it was made in accordance with an established practice which dictated materials, technique, form and content. Like many ancient pots, it is an example of work that exemplifies the very best of tradition, without apparently stepping outside the conventions of the time.

Some of these traditions have lived on, with the Chinese pottery of the Sung and T’ang dynasties inspiring many contemporary practitioners. An obvious example is Gwyn Hanssen Pigott, who, in her 2005 retrospective exhibition mounted by the National Gallery of Victoria, displayed examples of her work alongside ceramics from the Kent collection.

Hanssen Pigott’s early career was built on the belief that these Chinese ceramics represented a high point in human achievement. This was a philosophy shared by Leach and also by her first teacher, Ivan McMeekin, who developed a love of ceramics during time he spent living in China in the 1940s and subsequently when he was living and working in England, most notably with Michael Cardew, in the 1950s.

As McMeekin’s first apprentice, Hanssen Pigott would inherit that belief, and it is therefore entirely fitting that she should be able display her ceramics near the works that have inspired her for much of her life.

Hanssen Pigott has gone one step further than this, by actually making arrangements of ceramics housed in the collection at the Freer Gallery of Oriental Art at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington.

These seven arrangements: ‘Still Life with Pickle Jar’, ‘Garden’, ‘Remembrance’, ‘Blue Parade’, ‘Trail with Pale Bowls’, ‘Float’ and ‘Studio’, obviously reference the type of groupings she makes with her own ceramics, for which she has become quite famous.

Of course, Hanssen Pigott isn’t the first artist to rearrange museum collections in order to make some kind of point. There is a long history of this kind of activity in the contemporary arts. For example, the English artist and film-maker Peter Greenaway has worked with several important European collections, as in his 1991 installation The Physical Self which utilised the collection of the Boymans-van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam. In 1998 this same museum had hosted the Swiss exhibition designer Harald Szeemann’s A-Historical Arrangements, where one could, for example, find a piece by Joseph Beuys juxtaposed with a Degas bronze and some contemporary office furniture.

In the early nineties the American artist Fred Wilson staged a highly influential exhibition titled Mining the Museum which examined the history of race relations by re-arranging the collection of the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore. I heard Wilson talk about his project at a lecture he gave at the University of Melbourne in the mid-nineties, where he spoke about bringing his background as an artist of both African American and American Indian descent to bear on the conventions of museum display.

By the deceptively simple device of placing objects together which were normally displayed in entirely different contexts — for example, one of the arrangements featured a cabinet containing ornate silver jugs and goblets, perhaps originally owned by a wealthy slave-owning family, amongst which some iron manacles had been placed — he made startling new connections in a collection which had hitherto been given over to a more familiar mode of display.

What projects like this have in common is a desire to construct a new and unexpected narrative out of the vocabulary of objects that inhabit the museum. Sometimes this story has a very real political or social point to make, as in Wilson’s project, at other times the connections drawn may be more abstract or poetic, or even trivial — simply window dressing on a grand scale.

The writer Lisa Corrin, who had made a detailed study of Wilson’s projects, describes museum-critical art as being a genre so familiar in the contemporary arts that it possibly deserves it own ‘ism’, as in ‘museum-ism’. Others have pointed out that the seemingly arbitrary re-arrangement of museum collections may simply be an egotistical display, an easy way for an artist or curator to inscribe themselves onto the fabric of the collection.

In the case of Gwyn Hanssen Pigott’s interventions – and here I’m quoting from a Smithsonian press release – she ‘ignore[s] place and date and focuses wholly on colour, form, pattern and relationship, [demonstrating] a curiously sympathetic approach to the taste of Charles Lang Freer who acquired most of the selected objects a century earlier.’

This begs the question as to how one could fail to be sympathetic to Freer’s aesthetic judgement in a project such as this, which, after all, involved making tasteful arrangements of objects Freer had collected, then displaying them in a museum that bears his name. Certainly, Hanssen Pigott may have aired certain objects from within the holdings that hadn’t seen the light of day for some time, although you surely don’t need the services of an artist to accomplish this task — that’s what curators are for. For all their beauty, elegance and gilt edged provenance, these works demonstrate the complicated relationship between object and image, appropriation and creation, inherent is museum-reliant projects such as these.

There is an apposite quote which the artist and writer Brian O’Doherty, who is also known as Patrick Ireland, places at the beginning of his article The Gallery as Gesture, where he quotes Goethe, stating: ‘The value of an idea is proved by its power to organise the subject matter.’

Whether working with objects she has made herself or manipulating existing collections, Hanssen Pigott has almost single-handedly created a genre of work, which is often – although I think erroneously – given the title of still life. Her work represents one of the few real innovations in Australian ceramics over the past few decades, and it’s certainly the only one I can think of that has had an international impact. The down side is that it also demonstrates the way an innovation can, within a very short space of time, become a cliché, which brings us back, in a somewhat circuitous fashion, to the concept of old and new.

This is because what Hanssen Pigott made new in the 1980s has now become a familiar device, so much so that I suspect many viewers no longer stop to consider either what impact her work has had on contemporary practice, or indeed what antecedents there may be to her groupings of objects.

For example, Roy Ananada, writing in the journal Craft South about the work of the glass artist, Wendy Fairclough, states that Fairclough’s inspiration is drawn from the traditions of still life. He goes on to note that images of the painter Giorgio Morandi adorn Faircloughs’ studio walls, and yet nowhere in his essay is there any mention of Hanssen Pigott. I’ve heard of historical amnesia before, but this is the critical equivalent of short term memory loss. Fairclough’s arranges many of her installations in a different way to Hanssen Pigott, for example tilting and balancing objects and placing them in a precarious relationship to their support, and therefore I don’t mean to suggest that Fairclough’s work is the same as Hanssen Pigott’s. Nonetheless, when one writes about the work of a crafts-based practitioner who arranges objects in a manner suggestive of a still life and adorns their studio with posters of Morandi, I think it fair enough that Hanssen Pigott at least get a passing mention.

In 1998 when I exhibited a work titled Object Lesson in the Adelaide Festival of Arts exhibition Offline,curated by Kevin Murray, the catalogue image described the work as being ceramics, whereas I actually had exhibited a photographic transparency on a light-box. My sly critique of the fad for object-arranging had back-fired. The language of advertising, given voice through the elegant photography of Earl Carter in a piece originally commissioned by Belle magazine for a feature article I shared with Hanssen Pigott, Prue Venables and Shiga Shigeo, proved to be so pervasive that it merged seamlessly with the objects. One began to lose any sense of where the objects ended and the image began.

It is this hegemony of the image, of objects arranged and depicted, that has led to many of the developments we now see in contemporary ceramics. The distancing of the viewer, whether it be in a photograph or in the gallery, lends a certain fine art respectability to things which otherwise might find themselves sitting in the kitchen cupboard.

This can be seen in the absolutely extraordinary attention that is given to the photographing of work, and even perhaps why the term photographing has been replaced by ‘documenting’, a catchall phrase which extends to the mandatory appearance of an essay about the work, these things being as important as clay or glaze, sometimes more.

It is here that we see one way the old is made new in contemporary ceramics; not by striving for a new form, in a continuance of the modernist project with all its restless creative drives, nor by embracing tradition, a word which is now often used rather pejoratively. It is in the way that real, solid objects are now quite easily confused with the shadows they cast. Sometimes it’s like they’re on TV.

If not simply seen in terms of old and the new, innovation is often posited as a dialogue between the staid and the cutting edge, or even the dull and the groovy.

In 1968 the Director the National Gallery of Victoria, Patrick McCaughey, writing about an exhibition of proto-funk ceramics by Bill Gregory at the Pinacotheca gallery in Melbourne, observed that:

‘[Gregory’s ceramics are] splendidly hideous and marvellously useless, taking the Mickey out of arts and crafts pottery ‘

In his review of the same exhibition, the philosopher and art historian Donald Brooks wrote that:

‘There are few spectator sports more agreeable than watching someone stride up to a holy cow and kick it in the slats so hard that the sawdust dribbles out. Studio pottery is just such a sacred animal, and Bill Gregory is the man with the deft boot his pots are absolutely useless as refreshing as drought-breaking rain after an aeon of cider jugs with bucolic bodies like boiled oatmeal and orchid jars in a sensitive toffee temmoku.’

In the late 1950s Brooks had rented the flat above Hans Coper at the Digswell Arts Trust in Hertforshire. He knew Coper well, even on occasion helping him out in his studio, and he was well-placed to observe the interplay between those English studio potters who more or less followed Leach’s approach and the modernist tendencies exemplified by Coper, Lucie Rie and others.

One of the few things I have gleaned from Brooks’ recondite and complex arguments is that art, to be art, must constantly be new, which may, or may not, be the same thing as saying art has to be innovative. By his reckoning, a great deal of what passes for art, and this includes much contemporary art and doubtless all contemporary ceramics, is not art at all, but something else entirely. Brooks’ ends his 1985 essay for Craft Australia, titled ‘(Real) art is not craft’, by writing that ‘ we do not need a full or definitive answer if our objective is only to distinguish between art and craft. For that limited purpose the criterion is clear. Craft is a product of action: art is not.’

For those of you wanting a quick answer to the art/craft debate, I thought I’d just throw that in to the mix.

Brooks leaves the question of what quality then distinguishes art un-answered, but I suspect he thinks it has more to do with thought than action, with the mind rather than the hand.

There is, however, another aspect to this equation, one that has less to do with grand theories of art and is simply based in fashion. In 1968, when Brooks was writing his review, Gregory’s ceramics were thought of as being groovy, irreverent and funky, poking fun at convention and the status quo — they were, to use the parlance of the day, ‘with-it’. Kicking holy cows was all the rage and there were precious few constraints on where one could sink the slipper.

That same year, 1968, Margaret Dodds returned to Australia from studying with Robert Arneson at the Davis campus of the University of California. She was one of the esteemed early group at the TB9 studios who, if not actually being around for the birth of Funk, at least got to hold the baby. In 1968 she found herself back in Adelaide living in a suburb called (predictably enough) Holden Hill, where she added a potent, West Coast authenticity to the development of funk ceramics in Australia.

Dodds’ ceramics were definitely groovy, in a kind of slack, off-hand, hard to pin down way that exemplified the early incarnation of funk, a style which was so different to the brittle and somewhat precious work which characterised the latter phases of the movement known as Skangaroovian funk.

Of course, in the beginning funk was not at all to the liking of the establishment. They had just got used to large heroic abstractions, first in painting and sculpture and then in clay, so the arrival of these strange, parodic objects was quite unsettling, like coming home and finding a garden gnome pissing on the leg of your dining table.

The 1966 November/December issue of Craft Horizons had a special supplement which contained reviews of three exhibitions of contemporary ceramics: the 24th Ceramic National at the Everson Museum of Art, Abstract Expressionist Ceramics at the University of California in Irvine and the exhibition Ceramics from Davis, held at the Museum West Gallery in San Francisco, which showcased works by Arneson and seven of his students; Gilhooly, Kaltenback, Shaw, VandenBerge, Unterseher, Walburg and the young Australian Helen Dodd, as Margaret Dodds was known then.

In his review of the Davis show, Joseph Pugliese noted that the catalogue essay stated that ‘Arneson is placed alongside Peter Voulkos as one of the artist/teachers bringing pottery back to the power it’s achieved during its long history as the most durable art form, and the most fragile. ’Pugliese counters with the observation that, and I quote’ this is an unfortunate introduction to the exhibition, because these two guys are interested in art, not pottery.’

Margaret Dodds told me that Arneson was annoyed with Pugliese’s review, and doctored a copy of Craft Horizons so that when the magazine was opened at the appropriate page a funny noise was heard.

It’s not a bad review by any means, but it also doesn’t lie down like a puppy and ask for its tummy to be tickled. He isn’t that flattering about Dodd’s work, writing that her cars are ‘ fun to look at, but should be bigger, or smaller, or something’, a criticism which I think is pretty lame. After all, you can’t just say ‘..or something’ — that’s just not trying hard enough, and secondly I think Dodds made her cars just the right size, because they were kind of like toys and I think that’s where they gained a feminine and also feminist quality, talking about boys and motherhood and all sorts of other oblique references, without being bombastic and keeping a sense of play about them. In an interesting aside, Dodds told me that her father worked for a time as a car salesman with the Adelaide firm of Wakefield Motors, so it seems that cars were woven into her personal history from an early time.

The really interesting thing about the review is that in 1966 Pugliese is already writing that Funk work is a bit dated. He ends by stating that

‘ one can reflect upon the overall sweetness, even coyness, of most of the exhibit. These young artists are too eager to ride the high-style wave. Only ten years ago a ceramics exhibition on the West Coast would have been characterized by powerful, aggressive, masculine pieces. This seems to have given way to a decorative effeminacy, which at its best only titillates. Maybe the revolution in ceramics is over and we don’t even know it.’

Regarding Pugliese’s comments, it’s always wise to try to get some idea of where the critic is coming from, rather than taking the criticism at face value. In this case, the short bio in Craft Horizons stated that ‘Pugliese is a potter, currently specializing in ceramic shoes (see Craft Horizons, September/October 1965) from 1957 to 1964 he was associated with the University of California, Berkley, where he taught the history of ceramic art.’

Ceramic shoes? Sounds funk to me, as funk as the shoes the artist Alex Danko made while he was a student at the South Australian School of Art in the late 1960s, during which time he had contact with Margaret Dodds. So, referring to the appropriate issue of Craft Horizons, one finds an image of a Pugliese ceramic shoe, in the company of an Arneson sculpture, a jar by Michael Frimkess and a Ron Nagle cup. By the way, Pugliese’s shoe was almost two feet long (!), which I guess puts his remarks about Dodds’ cars being the wrong size in some sort of context. Keep in mind that we are having a serious discussion here about a man that makes big ceramic shoes criticising the work of a woman who makes little ceramic cars.

This Premier Pottery vase in the shape of a shoe, made in Adelaide towards the end of the 1800s, represents very different social values to those embedded in funk. It spoke of comfort and the ability to purchase and enjoy an item which was not entirely functional — and to this extent the values are arguably the same — but it most certainly would not have stood for lefty-politics, feminism, social activism, anti-war sentiments and an interest in mind altering drugs. The Premier Pottery shoe was a deeply middle-class object, or maybe these days one would say aspirational.

It would not have been bought by those on the top rungs of a settler society; those ceramics would have been made in porcelain and imported from England. However, this shoe was one step up (!) from purchasing purely necessary items like this Twernack jar, also made in Adelaide about 1877. We now see a pot such as this in an entirely different light, more as an object of nostalgia, an attitude even held, I would hazard a guess, by many contemporary potters. Whether that same attitude would extend to a similarly functional, working- class object like a sixteenth century Tamba-ware jar is predicated not so much on the intrinsic aesthetic value of the item, but rather of the history of the impact of Japanese ceramics on Western potters.

Early Australian pots, like this salt-glazed demi-john made in 1870 by Hindmarsh Pottery, were only crafted to the extent that function dictated. They had a job to do and they did it, proletarian to a fault. As such, they represent the kind of pot that is most marginalised within contemporary ceramic practice, yet they hold within them the possibility of real transgression, of resistance, far away from the spectacle of the contemporary arts. What I’m referring to is tradition.

The interesting thing about tradition is that it hardly ever gets a mention in the official discourse of the arts. Just as I trawled through the mission-statements of arts organizations to be confronted with the word innovation at every turn, I found a complete absence of the word tradition. It didn’t appear once. Why is this?

Maybe everyone assumes that tradition is just out there, like the air, and it doesn’t need to be mentioned. Maybe there is an assumption that all artists and craftspeople will be thoroughly trained in and informed about their tradition, their craft, before they go forth and innovate. Maybe the concept of tradition is seen as a bit old-fashioned and embarrassing and if no one talks about it will all just go away.

The problem with tradition, at least in Australian ceramics, is not that it’s holding us back, but rather that we don’t engage with it enough. For a start, the vast majority of the first generation of post-war studio potters completely overlooked the vernacular tradition of Australian folk pottery, moving straight to an Anglo Oriental model based on what I would counter was a mis-reading of Leach. As long ago as the early sixties the Australian potter Ivan Englund, in an article titled ‘Does Tradition Matter’, wrote that:

‘In Australia the lack of a pottery tradition is recognised and some potters wonder if their task is made more difficult because of this. Pottery making was not one of the tasks attempted by the early settlers nor did the native aborigines make pots. And in the intervening 175 years no lasting efforts were made, and our pottery needs were provided for by imports from England ‘

This simply isn’t true. In the early 1980’s I spent several years working in a traditional family owned pottery, Bennett’s Magill Pottery in Adelaide, that had for five generations and well over a hundred years been making the same sort of functional wares that they make today, and there were dozens of such potteries scattered all around the country.

What Ivan Englund was actually saying was that the Australian ceramic tradition simply didn’t accord with the dominant theoretical discourse of the time, which was based on Leach’s writings. Put simply, there was something about this kind of pottery that didn’t seem to fit with ideas of how the studio ceramic project could be progressed, and so it was simply ignored.

From this distance, it’s hard to imagine how such a beautiful tradition of folk pottery could be overlooked, but the reason is simple. It wasn’t seen as being innovative, and it wasn’t fashionable.

The most valuable lessons that these ceramics can offer is that they rather reverse the current trend of the hierarchy of values we now consider normal in the creative process, where meaning is privileged (and don’t we see this again and again in teaching situations) whereas these objects are first and foremost about function. Their form follows their function, and the meaning is something that is variously constructed by the social conditions of the time. The odd thing is that this doesn’t make them any less interesting objects than the most deliberately meaning-laden contemporary ceramics.

I’ll end by discussing a couple of projects I’ve been involved in, and considering what this work might mean in this discussion about innovation.

In the mid-nineties I met up with the Melbourne-based ceramic artist Steven Goldate when we were both at the Victorian College of the Arts, in the days when the VCA had a ceramics course.

We started to play around with a primitive computer modelling program Steven had downloaded as freeware off the web. It was called Lathe, and that’s what it did, performing a very basic lathing and wire-framing task.

Rather than just continue to feed in random lines for the program to lathe, we decided to look around for some information (data) that had a certain logical, and poetic, consistency when applied to this program. There were obvious connections to cartography, with grids and maps and globes. In one of those fortuitous co-incidences, someone had pointed me towards the Mitchell Library in Sydney, and had told me to look at the floor in the lobby which bears the image of the Tasman Map.

Steven and I started doing a lot of research into the Tasman Map, and the history and indeed the meaning of cartography, both in its techniques and in what maps mean for those that do the mapping, and indeed for those that are mapped.

We took data from the Tasman map and fed it into this little program, and made our first Tasman images. Steven then bought a better program and a bigger computer — one with a whole eight megabytes of RAM — and we continued to make slightly more elaborate images. At a certain point Merran Gates, then at the Canberra School of Art, heard about the work and invited us to participate in an exhibition she was curating for the Asialink centre at the University of Melbourne, called Patterning: Layers of Meaning in Contemporary Art.

Work from the Tasman project was included in several more touring shows, it was shown in the major gallery at RMIT Storey Hall, and as a fitting end to the project the final Tasman work was bought by the Art Gallery and Museum of Tasmania through the Plimsoll bequest. All in all this project lasted about ten years, it developed quite a corpus of information and artefacts, including a research document outlining all the historical and technical publication relevant to our research.

While Steven and I slowly became aware that this project was pretty unique, the vast bulk of the information we were working with was technical or historical in nature, so in a way the Tasman images, or virtual ceramics as Steven likes to call them, were simply a result of the data we were working with. I’m not sure if I’d describe this process as one of form follows function, but I think that part of the delight I had in this work was that it wasn’t at all like the stereotypical art-making process where one stares at the canvas or the clay, striving to make an individual and meaningful mark. In a way it was much more like making a functional object, except in this case when the function, that of explicating data, was removed, you were just left with the images. I also think this was key to a successful collaboration, in that if we had had to make joint aesthetic decisions based on personal taste the project would have come unstuck very quickly. Working in this manner, there was a kind of distancing between our own egos and what we made, and again I think there are parallels here in the making of functional ceramics.

For those who are interested, there is a link to a virtual gallery and essays associated with the Tasman project online at www.damonmoon.com.

For the last seven or so years, my work has mainly concentrated on a deep engagement with the traditions of Anglo-Oriental ceramics, both in an academic sense and in the pots I have been making. Some might see this type of work as being quite different to the Tasman project, or indeed a number of other projects or groupings of work with which I’ve been involved, either as a maker or curator or writer/researcher. I actually don’t see it this way, in that this current work is information-rich and thoroughly grounded in research. Looking at the impact of Leach on the development of Australian studio-pottery for my doctoral research made me want to make these kind of pots – it was just another way of knowing.

I guess I’ve pushed the work pretty far in terms of the techniques of making, for example using traditional Japanese-style hand-wheels to form the ware and gathering raw materials for the clays and glazes. I’ve found it interesting to see that when one works in this way, you end up with results that look like old Chinese or Japanese pots, simply because that’s what the techniques, the data you input, leaves you with.

So another similarity to the Tasman work is in the sense of distance between myself and the work. What there isn’t is a signature style, because I have a horror of being known as the person who makes bottles or beakers or bowls in this or that shape with the nice little line around them, or that sit in groups, or that are ironic and look like Toby Mugs or something.

If I can have any personal claim to innovation — a term which I think is pretty meaningless — it’s primarily to be found in the way I work, rather than in what I make. And, all in all, I still think it would be preferable if this word was done away with. I’d far prefer to see terms like quality, intelligence, humanity and even beauty, over innovation.

Damon Moon

Willunga 2009

The above quotes were all sourced from the official websites of the named arts organizations in late 2008 and early 2009.

- Lisa Corrin Mining the Museum: An Installation by Fred Wilson The New Press, New York 1994

- Frans Boenders quoted by Debora J. Meijers ‘The Museum and the A-Historical Exhibition’ Thinking about Exhibitions edited by Rosa Greenberg, Bruce W. Ferguson and Sandy Nairne, Routledge 1996

- www.asia.si.edu/press/prParades.htm accessed June 2009

- Goethe quoted by Brian O’Doherty ‘The Gallery as Gesture’ Thinking about Exhibitions ibid

- Roy Ananda ‘Wendy Fairclough’ Bulletin issue 4 June-July 2008 published by CraftSouth

- see feature article ‘Neutral Ground’ Belle: Design and Decoration No. 113 February-March 1996 Australian Consolidated Press Homemaker magazines

- Patrick McCaughey quoted in Judith Thompson, Skangaroovian Funk Art Gallery of South Australia 1986

- ibid

- Donald Brooks ‘(Real) art is not craft’ originally published in Craft Australia # 1, p. 108 — 109.

- Joseph Pugliese ‘Ceramics from Davis’ Craft Horizons Vol. XXVI November/December 1966

- ibid

- ibid

- ibid

- Ivan Englund ‘Does Tradition Matter’ Pottery in Australia Vol. 2 No. 2 October 1963